Kenro Izu: Seduction

Foreword

By Eikoh Hosoe, July 2017

The first time I saw Kenro Izu’s platinum prints was twenty-seven years ago in the summer of 1990. I was visiting with Howard Greenberg at his gallery in New York’s Soho neighborhood. The prints were kept in a special drawer and Howard proudly pulled them out to show me. They included delicately textured landscapes made of the Great Pyramids at Giza in Egypt, ancient Mayan ruins in South America, and Stonehenge in England—among the many “sacred places” Izu has spent much of his career documenting—as well as a selection of meticulously composed eloquent forms of floral still lifes.

I was impressed by the quality of Izu’s platinum prints which, unlike the vintage nineteenth-century versions with which I was familiar, displayed deep and rich blacks and a seemingly infinite range of tones between shadow and light. But what struck me the most at the time was the sense of spirituality in his work.

Howard explained to me that Izu made only contact prints from the original negatives created using his signature custom-made 14 x 20-inch Deardorff camera made specially for him in 1984. They were among the best prints I had ever seen and I had to have some. I am not sure, but I might have been the first Japanese collector of Izu’s platinum prints.

I did not meet Izu himself until the following year in 1991 at an exhibition of my work at the International Center of Photography in New York. He told me then that he had first visited New York in 1971 when he was a college student in Tokyo, and that he never returned to school. I can easily imagine that the excitement of New York was quite seductive to a young twenty-year-old with artistic aspirations.

By the 1990’s, Izu was already showing his fine work regularly at Howard Greenberg Gallery and other galleries in the U.S. But, his work was not as well known in Japan even though he had had two critically praised exhibitions in 1991 and 1992 at the Zeit Photo Salon in Nihombashi, Tokyo. I thought I could help introduce his images and the exquisite quality of his prints to a new photography audience in the country where we had been born and raised.

The first opportunity came in 1996 when the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts (K’MoPA) in Japan—a museum created exclusively for the photographic arts and where I have served as its director since its opening in 1995—hosted an exhibition, Light Over Ancient Angkor, which featured sixty-five of Izu’s platinum prints made from his series of photographs of the magnificent monuments at Angkor Wat in Cambodia. The “Angkor” photographs explored the intertwined themes of the fragility of civilization and the resilience of nature and the transcendent platinum prints elegantly conveyed the substance and spiritual gravity of Angkor Wat’s unique beauty and aura of peacefulness, which Izu explained to me he felt deeply throughout his time there.

Izu’s photographs fit perfectly with the interests of K’MoPA which is guided by three basic collecting and exhibiting principles: photographs made in the affirmation of life; the eternal quality of platinum prints; and the work of the next generation of young artists. Izu’s work celebrates a boundless sympathy with all forms of life, whether it is in his photographs of ancient monuments and landscapes, still lifes of flowers, or explorations of the human body. In addition to guiding his career as a photographer, Izu’s desire to express an “affirmation of life” and the importance of spirituality also inspired him to start a non-profit organization, Friends Without A Border, in 1996, which built, funded, and managed a free children’s hospital in Siem Reap, Cambodia, that opened in 1999. He still leads the organization to this day and most recently it opened a free children’s hospital in Luang Prabang, Laos, in 2015. Given Izu’s commitment not only to affirming life but also saving it, as well as his devotion to the platinum printing process, it is difficult to think of any other photographer whose work fits so naturally into the collection and mission at K’MoPA. To this date we have hosted a total of four solo exhibitions of his photographs including Sacred Places of Asia (2001), Bhutan: Sacred Within (2008), and most recently Eternal Light (2016) which featured Izu’s photographs documenting the people of India who live on the fringes of society.

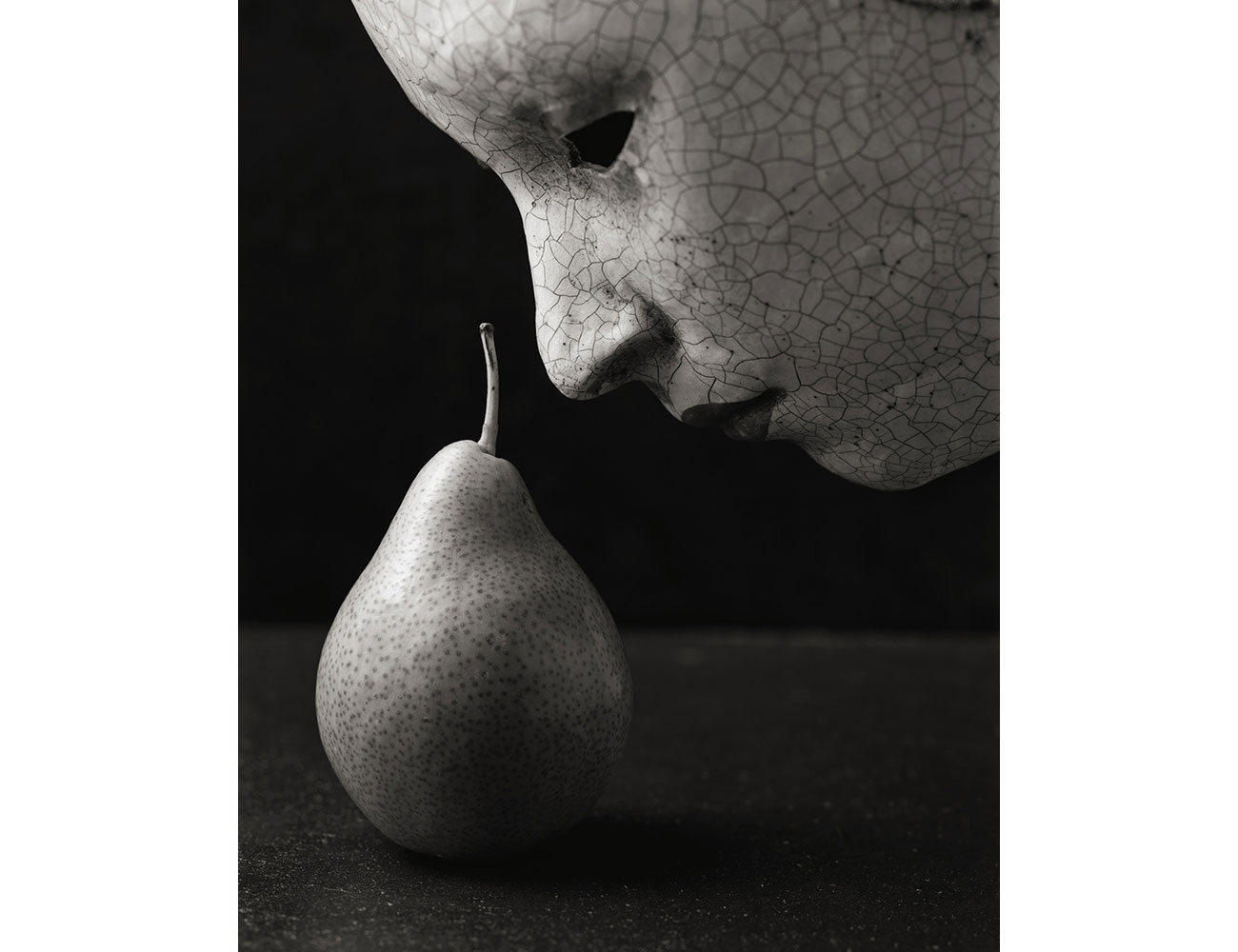

This newest book of Izu’s photographs features his still lifes and nudes. It includes work created at various times over more than thirty years from four series: floral still lifes, nude studies, still lifes with pears, and “Blue.” The last group was photographed from 2001 to 2004 as an homage honoring the centennial of Pablo Picasso’s “Blue Period” (1901–1904). All the photographs in this book were made using film cameras, ranging from 8 x 10 inches to 14 x 20 inches. Despite the advent and proliferation of digital technology in photography, Izu still continues to use these same cameras for all his work, cemented by his love of contact platinum prints from the original negatives that started with his first still life photograph in 1985.

As a photographer—as an artist—Izu approaches every subject in search of what can be described as the most translucent image possible, like that of his own reflection in still water. His photographs combine a duality of severity and tenderness that makes me think he is seeking an answer to the meaning of life itself—with both strict discipline and, at the same time, a restful spirit of peace and tranquility.

The resulting elegance of his images with their refined compositions of form, light, and shadow, fully realized in the exquisite depths and tonal ranges of his platinum prints, can easily mislead the viewer to a superficial admiration of the simple beauty of his art. But I advise you not to miss—in fact, to actively seek out—the most important principle that flows as a natural and spiritual current through all of Izu’s photographs, whether they are of sacred places in the world, portraits, or the still lifes and nudes in this book: the profound importance of the beauty and meaning of life itself. More than anything, that is the lasting impression of the photography of Kenro Izu.