A Ghost Town, Beautiful and Melancholy

By Malcolm Daniel

Gus and Lyndall Wortham Curator of Photography

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Ash was now falling, although not yet thickly. I looked back: dense blackness loomed behind us, pursuing us like a torrent poured out over the earth. “Let us leave the road while we can still see,” I said, “so that we won’t be knocked down and crushed in the darkness by the crowd around us.” We had only just sat down when darkness fell, a darkness not like a moonless or cloudy night but like a closed room when the light is extinguished. You could hear the howls of women, the wailing of babies, and the shouts of men: some were calling for their parents, some for their children, some for their spouses trying to recognize their voices; some lamented their own misfortune, others that of their relatives; there were some who in their fear of dying begged for death; many raised their hands to the gods; still more concluded that there were no gods left and that harsh and everlasting night had descended on the world. […] A little light returned, but it seemed to us a sign, not that day was coming, but that the fire was close by. Yet the fire actually remained some way off; darkness returned, and ash started falling heavily.Again and again we got up to shake off the ash, otherwise we would have been covered and even crushed by the weight.1

The terrifying scene described by Pliny the Younger in a letter to the historian Tacitus some twenty-five years later is the only surviving eyewitness account of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD.In truth, despite the pandemonium and shower of ash he described, Pliny was a relatively safe twenty-two miles upwind from Vesuvius.Across the Bay of Naples, just five miles downwind from the volcano, Pompeii was being blanketed by more than thirty feet of ash and rock, and on the second day a pyroclastic surge of super-heated gas and ash destroyed anyone and anything that had not escaped or been buried during the eruption’s first day.

In the days before Vesuvius let loose, Pompeii was a bustling Roman seaside town of well-appointed villas.Today, it is a tourist mecca explored by some two-and-a-half million visitors each year who poke their heads in the site’s homes and wine shops, bakeries and baths, walk the streets and public squares, and imagine the lives of ancient Romans. Like every archaeological dig, Pompeii is a time capsule of sorts, where artifacts of the past gradually emerge to paint a partial picture of life at another time. Elsewhere, the unfathomable riches of King Tut’s tomb speak vividly of ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife; the discovery of the “terracotta warriors” has opened a window onto the hierarchy of civilian and military society at the birth of imperial China; and the remains of Machu Picchu give clues about the organization of Inca society even as they leave much unanswered. But there is no time capsule of daily life quite like that which remains still partly buried at Pompeii—a time capsule sealed before anyone could consider what was or was not worthy of preserving for the future, what was needed for the journey ahead and what could be left behind. Loaves of bread at the bakery and pornographic frescoes in the brothel, the amulets of a sorceress and instruments of a surgeon, a satchel of gold coins and exquisite jewelry, a humble housekey and well-preserved villas adorned with exquisite mosaics, painting, sculpture, and furniture—it’s all there. But neither the daily activity of its onetime inhabitants nor the throngs of modern travelers are Kenro Izu’s subject. Instead, his vision of Pompeii is one of vast loneliness, of heartbreaking emptiness, of post-apocalyptic silence—as much a caution about the future as a picture of the past.

For some four decades, Izu has traveled the world seeking out people and places of spiritual significance from Teotihuacan to Tibet, Angkor Wat to Easter Island, Stonehenge to Borobudur, spending the time required for such sacred places to work their magic on him before he set about working his magic with the camera. Time has long been an essential element in Izu’s photographs. Days often passed as he searched for the right vantage point and the most expressive conditions of light and weather; even then, the process was slow. He carried a gargantuan tripod-mounted view camera that holds negatives 14 x 20 inches, a camera that rivals in scale the one used by Francis Frith, whose views of Egypt from the 1850s first inspired him. With such a camera, even the exposures engaged time in an unfamiliar way, sometimes requiring the lens to be open for as much as twenty minutes. Contact-printed as platinum prints, his mammoth negatives yield an astonishing amount of detail and beautifully render the full tonal scale and an uncommon quality of light.

Not only do his Pompeii pictures, gathered here as “Requiem,” depart technically from his previous work—Izu used a medium-format digital camera with a wide angle lens in addition to his enormous view camera—they differ in a more essential way: here the project began with an idea, and the artist staged the scenes before his lens in order to realize that vision. Pliny wrote that many feared “that there were no gods left and that harsh and everlasting night had descended on the world.” It’s a sentiment now easy to imagine and one that haunted Izu. The sword of Damocles hangs over each of us, a fragile thread keeping us in the land of the living. Not likely a volcanic eruption, but other hazards threaten to snip that thread: the stray bullet, the cancerous cell, or the drunk driver might take us out one by one, or, on the global level, the “harsh and everlasting night” may come in the form of nuclear annihilation or climate change and mass extinction. This is what led Izu to shape an expression of that fearful possibility amid the ruins of Pompeii, helped by the haunting forms of its ancient inhabitants.

Archaeologists have found mummified remains in burial sites around the world, but only at Pompeii have the bodies of the living been preserved in so eerily affecting a way. Discovering occasional voids in the volcanic mud and ash, nineteenth-century archaeologists poured plaster to fill the space left by the long-since decomposed soft tissue of bodies engulfed by the eruption almost 2,000 years ago. Writing in 1868 about Giorgio Sommer’s photographs of those recently formed casts, one critic aptly made a connection between such plaster figures and photography itself, remarking that the pictures revealed “with a fearful fidelity the dreadful agonies of some of those who perished at Pompeii, and… it is very difficult to divest the mind of the idea that they are not the works of some ancient photographer who plied his lens and camera immediately after the eruption had ceased, so forcibly do they carry the mind back to the time and place of the awful immurement of both a town and its people.”2

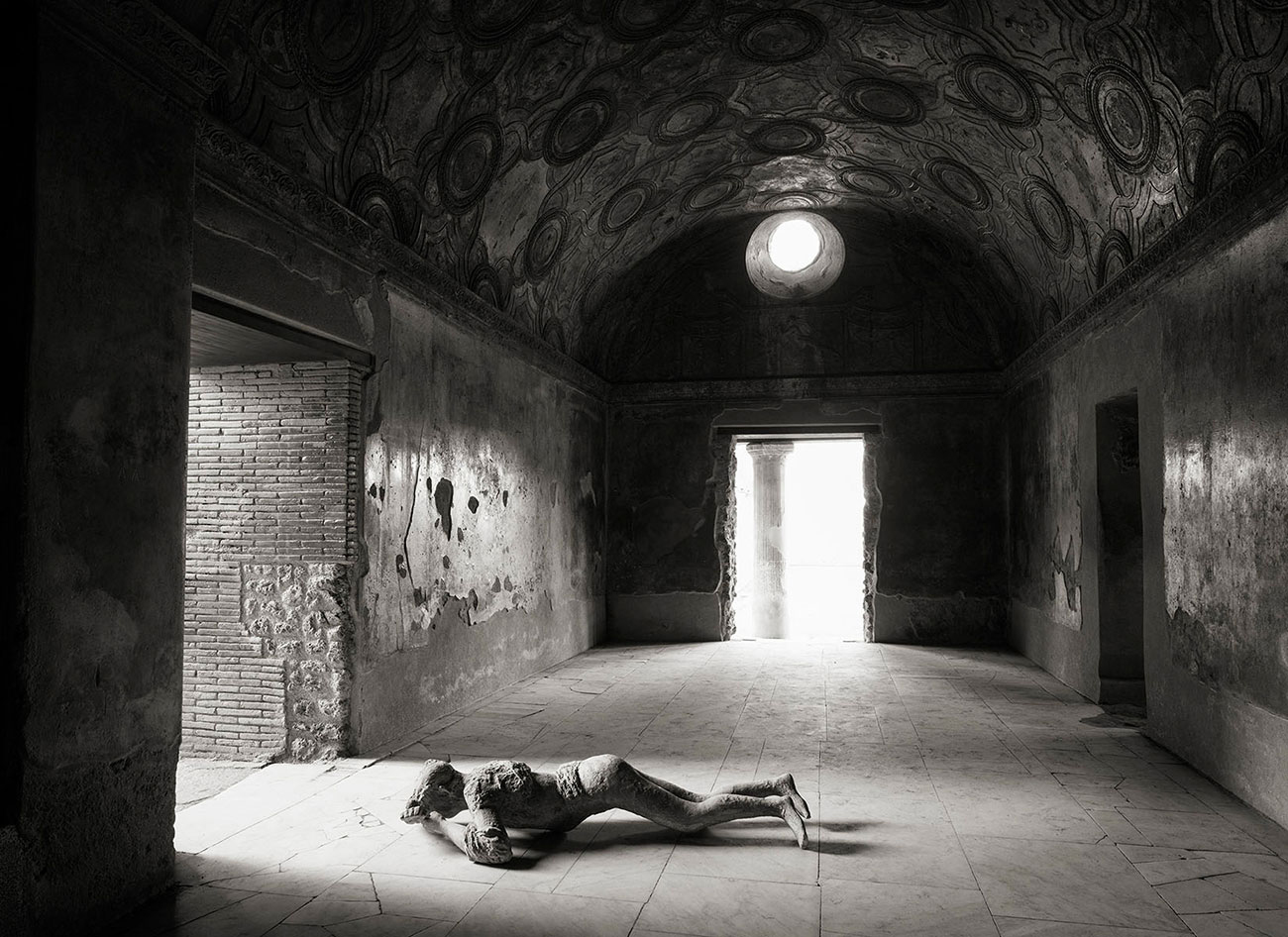

Rather remarkably—no doubt the result of quiet diplomacy, immense patience, the esteemed quality of his photography, and his well-known humanitarianism—Izu was granted permission to have those lifelike casts (actually casts of the original casts) positioned amid the ruins of Pompeii. The ghostly forms of the city’s original inhabitants become the actors in Izu’s theater. A young man crouches in a fetal position, hands covering his face. Two women seem to comfort one another in final embrace. A guard dog left chained by the House of Orpheus curls up in final suffocating agony. A figure lays prone, head on arms as if asleep.

Little concerned with the current trends of contemporary art and photography (no wall-size face-mounted color photographs here, thank you very much), Kenro Izu is at heart a Romantic, in awe of nature, of the past, of the sublime and the beautiful, of art’s ability to express and elicit deep emotions. And like the Romantic artists and landscape architects of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Izu has found ruins to be a powerful emblem of both the beauty and fragility of life, the extraordinary accomplishments of civilization and their ultimate surrender to the forces of nature and the passage of time.

It is neither the living city nor the tourist site that Izu has photographed, but rather a ghost town, beautiful and melancholy. In recent years, other photographers have traveled to the thousand-square-mile “dead zone” around Chernobyl and have found nature reclaiming the apartment blocks, schools, amusement parks, and government offices that were abruptly abandoned and remain almost entirely devoid of human activity—the literal meltdown that Izu fears. A poet, not a documentarian, however, Izu emphasizes in “Requiem” the beauty of civilization in peril rather than the politics of failed Soviet utopian ideals. Those plaster figures in his photographs are not characters in a diorama; they are stand-ins for ourselves. Like the last person on earth surveying the ruins of a once glorious world, the viewer enters these exquisite photographs of Pompeii and weeps, not for the past, but for the future.

1 Pliny the Younger, “Letter 6.20 [13-16],” translated by Benedicte Gilman. In Barry Moser et al., Ashen Sky : The Letters of Pliny the Younger on the Eruption of Vesuvius. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007, p. 33.

2 John Werge, “Photography and the Immured Pompeiians,” The Photographic News, September 4, 1868, p. 427.